by David Jin

Recently, I wrote an article about the accusations of inefficiency leveled at Julio Jones. The primary criticism analyzed is his relatively lower touchdown count compared to his receiving yards. However, a player’s own statistics don’t tell the whole truth about the outcome of a game. Football is a team sport, and how a player makes others around him better can be just as important as how well he plays himself. That said, let’s look at a common defense of Julio Jones’s statistics: by being such a dangerous receiver, he opens up other scoring opportunities for his teammates.

To perform this analysis, we look at all of the games which Jones played between 2011-2018, and the offensive touchdowns scored. For a player to get truly useless receiving statistics, he must catch passes leading to no scores, either a punt or a turnover. Given the primary criticism of Jones’s ineffectiveness in scoring touchdowns, we must make this stricter, and say that even contributing to a drive which ends in a field goal is insufficient. With this in mind, let us look at all of the “aidable” touchdowns the Falcons scored from 2011-2018. A touchdown is deemed aidable if it passes three criteria. Firstly, the touchdown have been scored by a teammate. We are interested in seeing how Jones helps his teammates instead of himself. Secondly, Jones must have been healthy and available for the drive. This means that all touchdowns scored while Jones was injured will be ignored. Thirdly, the touchdown must be either a rushing or a receiving touchdown, as fumblerooskis are illegal and Jones’s receiving yards were not deliberately gained to aid an offensive fumble return touchdown.

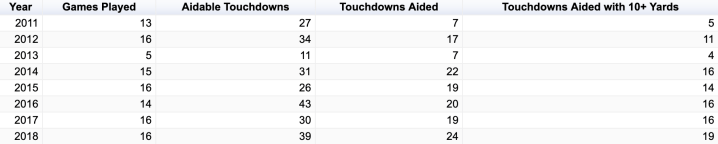

Between 2011-2018, the Falcons have been one of the NFL’s hottest offenses, and Jones has been a part of squads that include legends like Roddy White and Tony Gonzalez, stalwarts like Michael Turner and Steven Jackson, which were conducted by Matt “Matty Ice” Ryan, whose ability to spread the ball in no doubt has made this possible (a few of these teams also included Jason Snelling, a personal hero of mine: an epileptic runningback). Jones has had plenty of touchdowns he could aid. This chart shows the season, number of games Jones played, the number of aidable touchdowns the team scored, the number of touchdowns Jones aided, and the number of touchdowns Jones aided with a reception of more than ten yards. The last column is an indication of the magnitude of the contribution to the touchdown; a one-yard catch on 2nd and 10 is not much aid to the drive. Thus, this criterion balances the total yardage of Jones’s contribution with its effectiveness in continuing the drive.

Jones’s rookie year was excellent, racking up 959 yards on 54 receptions with eight touchdowns in 13 games. However, he only aided seven touchdowns, and of those seven, only five included a reception of ten yards or more. Perhaps it was offensive coordinator Mike Mularkey’s (relatively) run-heavy Erhardt-Perkins system, or just the team feeling out Jones’s skills, but his contribution to others’ touchdowns would be the lowest of his entire career. However, his next few seasons would start to establish a regular pattern of contributions, something that would occur regardless of whether his offensive coordinator was Dirk Koetter, Kyle Shanahan, or Steve Sarkisian:

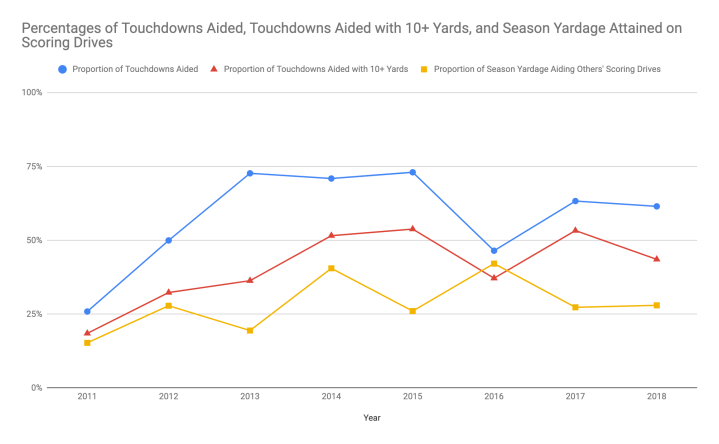

Firstly, I would like to bring your attention to the 2016 season, where Jones’s proportion of touchdowns aided fell precipitously. While it could be attributed to the scheme of Kyle Shanahan which created more touchdowns overall and giving Jones more opportunities to contribute yardage, it is more likely that this drop occurred because of Jones’s multiple injuries through which he played. It is interesting to consider what Jones could have contributed had he been healthy, especially the proportion of his season yardage that aided others’ scoring drives, the yellow (square-point) line. This line is also a very telling statistic. During the 2012, 2015, 2017, and 2018 seasons, Jones contributed around 26-28% of his overall season yardage to others’ scoring drives. During these seasons, he personally scored 10, 8, 3, and 8 touchdowns, respectively. This means that regardless of the number of touchdowns Jones personally scored, he has consistently contributed the same proportion of yardage to his teammates’ scoring.

How do Jones’s contributions rank in comparison to the rest of the league, or in comparison to wide receivers who score many touchdowns? To answer this question, we performed a similar analysis the statistics of the season leaders in receiving touchdowns between 2011-2018.

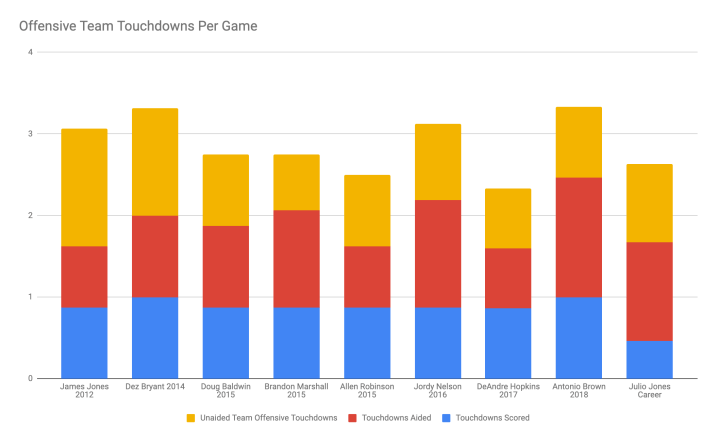

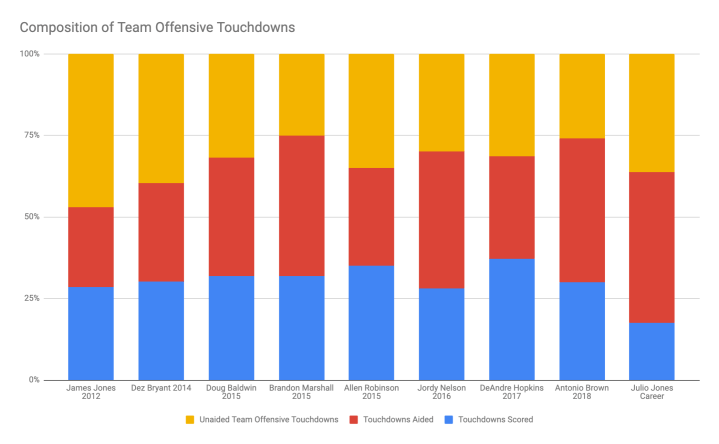

As with the previous analyses, the only touchdowns included in the unaided team touchdowns (yellow portion) had to satisfy the three aidability criteria. This chart notably does not include the record-setting seasons by TE Rob Gronkowski in 2011 and TE Jimmy Graham in 2013; these were not included because the tight end position is still different enough compared to the wide receiver position that a fair comparison would be impossible. Obviously, at around 7.4 touchdowns per 16 games, Jones’s average receiving touchdowns scored personally is far behind these leaders. However, given the amount of aid he has provided to his team’s offensive touchdowns when he is suited up, he leaves his mark on touchdown scoring as much as the league leaders on this list, and more than James Jones, Allen Robinson, and DeAndre Hopkins in their seasons leading the league in receiving touchdowns. To ensure a fair comparison between teams’ scoring abilities, we also created a chart showing these relative contributions as a proportion:

Over the course of his career, Jones has aided 46.2% of his team’s touchdowns when he plays, leading all players on this chart in that (red) portion (mean=35.2%, standard deviation=7.3%). In total, Jones has left his mark on 63.7% of his team’s offensive touchdowns when he plays, a number that is comparable to league leaders in receiving touchdowns (mean=66.8%, standard deviation=7.2%).

I believe that this analysis begins to disprove the idea that Jones’s play is fundamentally flawed because he is unable to get receiving touchdowns. His contribution to the team is immense, and this analysis lends credence to the arguments of his supporters that his presence sets up touchdowns for other players. Unlike some previous star receivers, he has not excessively griped when he does not receive the ball in the end zone. Perhaps this is confused for complacency. But how can it be easy to be get agitated when you’re helping your teammates score over and over again?

Many thanks to fellow HEX Sports Group author Derek Salvucci for his help in developing this analysis, and Pro Football Reference, as always, for the statistics used in this analysis.